Yoga Tips For Holiday Digestion

As a vegetarian married to a vegan, I’ve grown accustomed to dealing with a great deal of well-meaning fretting from both my mother and my mother-in-law when my husband and I visit our families for the holidays. My mother brought me up on the USDA’s “Four Food Groups” nutritional model of the 1970s; in her mind, a proper dinner consists of a meat-based main dish accompanied by a vegetable, a plant-based starch, and white rolls with margarine. There are no exceptions to this rule, and she prides herself on having provided me, my three sisters and our father with a “proper” dinner every single night for 20 years. And don’t get me wrong, I appreciate it.

As a vegetarian married to a vegan, I’ve grown accustomed to dealing with a great deal of well-meaning fretting from both my mother and my mother-in-law when my husband and I visit our families for the holidays. My mother brought me up on the USDA’s “Four Food Groups” nutritional model of the 1970s; in her mind, a proper dinner consists of a meat-based main dish accompanied by a vegetable, a plant-based starch, and white rolls with margarine. There are no exceptions to this rule, and she prides herself on having provided me, my three sisters and our father with a “proper” dinner every single night for 20 years. And don’t get me wrong, I appreciate it. The idea of coming home from a long day of work and cooking a full dinner for six people even once a week makes me want to get into child’s pose and stay there. My husband’s mother was a pediatric nurse who often worked the evening shift, so his father—not a man who grew up cooking— was usually responsible for providing nightly dinner for three growing boys, on a budget. Unsurprisingly, to this day it is hard for my husband’s parents to conceive of a family dinner that doesn’t revolve around two to three pounds of hamburger incorporated into a recipe off the back of a box.

Like many loving mothers of adult children, my mother and my mother-in-law remain consumed with concern about what and when and how often my husband and I eat, especially when we’re in their homes. Cooking and serving food is a way of showing love, and it is frustrating to both of them to be denied the pleasure of making our favorite childhood foods now that we no longer eat many of them. Even more so, I think their concern stems from a phenomenon common to non-vegetarians, namely, a sincere worry that vegetarians and vegans simply aren’t getting sufficient nutrients. It’s been well over a decade since we both stopped eating meat, but at family functions the question still arises with seemingly unassuageable vexation: “Will there be anything for you to eat?!” Unsurprisingly, the issue assumes an even greater intensity around the holidays, particularly Thanksgiving (which, in my husband’s family, is celebrated as less of a holiday and more of a 14-hour competitive eating decathlon).

Two years ago, after remaining at home in New York City for Thanksgiving for logistical reasons and fielding agitated FaceTime calls from both of our mothers –-“Did you get enough to eat?!” (his) “What did you even eat?!” (mine), we decided to put our parents’ minds at rest once and for all. After a bit of persuading, we convinced our families to let us cook them vegetarian/vegan holiday meals last year—we visited his family for Thanksgiving in mine for Christmas— to close the book once and for all on the question of whether it’s possible to uphold the American holiday tradition of gluttonous overindulgence without eating animal products.

They were skeptical at first, but after enjoying seconds of my Brussels sprouts gratin, thirds of his mushroom-sage stuffing, and subsequently passing out on the couch only to awaken two hours later for one more slice of dairy-free pecan/pumpkin pie, we had them convinced: it’s not only possible to overdo it at a vegetarian Thanksgiving, it’s positively easy. As a yogi, I try to practice brahmacharya—sometimes defined as discipline over the impulse towards excess—but I am only mortal, and my self-restraint tends to fly out the window when confronted with garlic mashed potatoes.

All of which is to say, whether vegetarian, vegan, pescatarian or omnivore, most of us have a tendency to overindulge at this time of year. I teach at a college, and by the time I’m finished with the fall semester I have usually attended at least four work-related holiday parties, having managed to resist housing a bucketful of my colleague Professor Yao’s home-made Chex mix at exactly none of them. Brahmacharya is all well and good, but you know what’s also good? My friend Dave’s praline pecans.

If you’re anything like me, dramatically increasing your intake of sugary, fatty and processed foods tends to wreak havoc on your digestive system. We can’t put a halt to holiday fun (who would want to?) and I, at least, probably cannot stop myself for reaching for that second White Fudge Oreo (they’re only in stores once a year!). Thankfully, asana and yogic techniques are available to aid and improve our digestion, as well as mindfulness practices which can help us truly appreciate the sensory ritual of eating. Read on for five tips for improving digestion with yoga this holiday season.

1) Add Twists to Your Asana Practice

Let’s not beat around the bush: between the eggnog and the port-wine cheese balls, I tend to consume a lot more dairy than usual during the holiday season, which tends to, um, cause my inner elves to slooooow down production in the ol’ toy shop, if you take my meaning. In other words, I get constipated, and when I do, I make sure that my on-the-mat practice includes plenty of twists. Just make sure you’re doing them correctly to aid in… efficient toy production.

Twists aid in the movement of waste through your colon, as long as you begin by twisting to the right side. Starting this way targets the ascending colon, helping it to stretch and send waste across the transverse colon. Then, when you twist to the left, your body encourages the waste to continue on to the descending colon and finally into the sigmoid colon, where it becomes ready for elimination. Try incorporating parivritta ardha chandrasana (revolved half-moon) and parivritta trikonasana (revolved triangle) into a warrior sequence, or add parivritta utkatasana (revolved chair) into a standing balance sequence.

2) Boost Your Agni

Agni is the Ayurvedic term for “digestive fire” (meaning your body’s capability to digest food easily and completely). Undigested or poorly digested food results in the body’s production of a toxic by-product called ama, which inhibits immunity. (For more on agni, ama, and boosting immunity with yoga, refer to our post “Yoga Hacks for Allergy Season” here.)

Healthy digestion requires strong agni, and strong abdominals beget strong agni. Asana that target the abdominal muscles include phalakasana (plank pose) purvottanasana (upward plank) utthtita trikonasana (extended triangle) and virabhadrasana (warrior) III. Strengthening the lower back muscles will contribute to your core strength, so make sure that your on-the-mat practice includes plenty of vinyasas (adho and urdhva mukha svavasana are both excellent for increasing back strength) as well as danurasana (bow), salabhasana (locust) and/or setu bandha sarvangasana (bridge).

In addition, try practicing the pranayama/asana hybrid agni sara. Agni sara (literally “essence of fire”) utilizes the solar plexus, lower abdominals and pelvic floor muscles, stimulating the digestive system and aiding in proper elimination of waste. You can view a step-by-step guide to agni sara here. For beginners: start in sukhasana or malasana and contract the lower abdominals. Breathe deeply into the belly and pelvic floor, pulling the navel firmly towards the spine on the exhale and relaxing the belly fully on the inhale. Three rounds of ten breaths—ideally on an empty stomach—are sufficient.

3) Utilize Pranayama to Reduce Stress

Over-indulgence in rich or sugary holiday treats, alcohol and/or gluten and dairy can result in bloating as well as constipation. But bloating can also be a by-product of stress, and stress can inhibit effective digestion. There’s a reason the gut is often referred to as the body’s “second brain.” Acute stress directs blood flow to away from gut to the brain and limbs, and chronic stress can cause imbalances in beneficial gut bacteria, as well as inflammation.

There are many aspects of yoga that reduce stress, but deep belly-breathing in particular releases tension in the abdomen, allowing for increased blood flow and aiding in digestion, which in turn reduces bloating. A simple breathing exercise that targets the belly is Dirga Pranayama, or three-part breath. To practice Dirga Pranayama, find an easy seat with a straight back and a hand loosely placed on your belly. Inhale deeply and slowly, imagining that you are filling your belly, ribcage, and upper chest completely. Then exhale equally slowly, “deflating” the upper chest, ribcage, and belly. (Note: of course, you cannot actually breathe into your belly! But you can feel the sensation of breathing into your belly by practicing Dirga Pranayama, which in turn can help your abdominal muscles relax.) Another effective way to feel the breath drop low in the body is to find a comfortable child’s pose with relaxed arms, and inhale slowly with the intention of feeling the sensation of expanding your lower back with your breath. If it’s comfortable for you, separate your thighs so that your belly can “flop” between them.

4) Plan Ayurvedic Holiday Meals

Happily, Ayurveda already involves eating seasonally and regionally, and many of the traditional holiday dishes associated with Thanksgiving and other holiday meals are already based around fall harvest produce in North America. Yams, Brussels sprouts, carrots and other root vegetables are all in season in the autumn and can contribute to a balanced holiday meal while supplying nutrients without reducing agni. Even potatoes—sometimes regarded as a blanket no-no in Ayurvedic cooking—can take their part on your table, as long as you prepare them according to your dosha: add oil or other fat for Vata, limit fat and add warming spices for Kapha. Potatoes are basically neutral for Pittas, so go ahead and have that second scoop!

In addition to eating seasonally, keep your holiday meal Ayurvedically sound by including the six tastes: sour, salty, sweet, pungent, bitter and astringent. The fatty, moist recipes associated with Thanksgiving dishes will help to balance the dry, cold Vata season in which the holiday falls. Just make sure you include bitter, pungent, and astringent tastes as well, to balance the flavor and nourish the dhatus. Ayurvedic holiday recipes, including Thanksgiving favorites, can be found here.

5) Try Following a Sattvic Diet

Following a Sattvic diet at points throughout the year can certainly ease radical eating disparities during the holidays. In Ayurvedic philosophy, there are three qualities, or gunas, that exist in all of nature: rajas, tamas and sattva. With regard to nutrition, these qualities manifest as stimulating rajasic foods (spicy, salty, or bitter tastes), enervating tamasic foods (bland, heavy tastes, or anything artificial or stale) and purifying sattvic foods (fresh, calming, and easily digestible).

The term sattvic can refer to an entire lifestyle of intentional ritual, meditation and philosophy. Serious yogis will often maintain a sattvic diet for months or even years at a time, or undertake a sattvic cleanse, which can be intense and should be conducted under the supervision of a professional Ayurvedic practitioner. But we can all add elements of sattvic eating into our daily diets to improve digestion and wellbeing. Here are some simple suggestions to get digestion back on track after a holiday meal, keeping in mind that you may need to make adjustments if you are currently eating to balance your particular dosha:

• Eat fresh, organic produce. Try to base meals around fresh ingredients and whole foods.

• Eat less meat. Try beans and lentils as alternate sources of protein.

• Cut down on refined sugar and processed foods. Consider honey or molasses as an alternative to sugar.

• Reduce your intake of alcohol and caffeine. Alcohol is enervating, or tamasic, and caffeine is stimulating, or rajasic. Reducing both helps to bring the both mind and the gut into a balanced, calm sattvic state.

• Pay attention to where and how your food is prepared. Truly sattvic food is prepared in a pleasant atmosphere, with intention and love. While this might not be practical for every meal, especially if you frequently eat outside your home, you can start by making one sattvic meal day for yourself every day, such as a simple breakfast of whole oats, fresh milk, and some honey or fruit.

While brahmacharya is certainly a virtue, even the most disciplined among us can fall prey to the perils of holiday revelry, leaving our tummies to pick up the proverbial tab. Happily, whether we’re planning ahead or looking back in regret, yoga and Ayurveda offer plenty of tools for soothing and regulating digestion. So, bring on those special edition White Fudge Oreos! After all, they’re technically vegan, and this year I’ll stop after one. Or two. Definitely not more than three.

For an intro to Ayurveda, please join us for Prema Yoga Therapeutics Essentials February 7 -March 1, 2020, or for a more in-depth explanation in our annual Ayurvedic Yoga Therapy Therapy Training.

—————-

Online Sources:

___________________________________________________________________________________

Molly Goforth is a yoga and meditation teacher and a student at Prema Yoga Institute. She specializes in accessibility and trauma-informed yoga teaching and practice.

An Interview with Erin Moon, PYI Graduate and Director/Co-Creator of the World Spine Care Yoga Project

As a student in Prema Yoga Institute’s Yoga Therapy Certification program, I had the privilege of undergoing a 50 hour training in Functional Anatomy under the tutelage of Erin Moon, a certified yoga therapist and Prema graduate, and director and co-creator of the World Spine Care Yoga Project.

World Spine Care created the Global Spine Care Initiative (GSCI) in 2018 as a community project, to “reduce the global burden of disease and disability by bringing together leading healthcare providers, scientists, specialists, government agencies, and other stakeholders to transform the delivery of spine care.”

I recently had the opportunity to sit down with Erin and ask her some questions about her work as a yoga therapist in general and the Project in particular in advance of World Spine Day, which will mark its eighth year of official celebration on October 16th. What follows are excerpts from that conversation.

As a student in Prema Yoga Institute’s Yoga Therapy Certification program, I had the privilege of undergoing a 50 hour training in Functional Anatomy under the tutelage of Erin Moon, a certified yoga therapist and Prema graduate, and director and co-creator of the World Spine Care Yoga Project.

World Spine Care created the Global Spine Care Initiative (GSCI) in 2018 as a community project, to “reduce the global burden of disease and disability by bringing together leading healthcare providers, scientists, specialists, government agencies, and other stakeholders to transform the delivery of spine care.”

I recently had the opportunity to sit down with Erin and ask her some questions about her work as a yoga therapist in general and the Project in particular in advance of World Spine Day, which will mark its eighth year of official celebration on October 16th. What follows are excerpts from that conversation.

—————————————————————————

PYI: What originally drew you to yoga therapy?

EM: It was a natural progression as the term came into greater recognition and regulation within the modern yoga community. I was grandfathered into IAYT partially because, like so many collogues, I had been and continue to work with every client with deep care and the approach of the holistic health paradigm that the ancient practices and philosophies of yoga provide. I felt it was important, as I furthered my education, to dive deeper into the intersection of the allopathic and holistic approaches to health and healing. As it does for so many others, the desire to deepen my training arose from personal trauma and the old adage “teacher heal thyself.”

PYI: While studying at PYI, what was your favorite module?

EM: I loved Yoga in Healthcare. In my 300hr training, before Prema, I focused on yoga and healing and then narrowed my focus to yoga and stress, specifically the neurobiology of stress. Yogic practices, I believe, work with stress in a very special way and provide our greatest opportunity for intervention through many, many tools. So getting a chance to learn from soma-psychotherapists, physicians and physical therapists who are also yoga therapists about what they have learned clinically was astoundingly enlightening.

PYI: When did you first begin to focus on spinal care?

EM: In 2015 I met the Clinical Director of World Spine Care (WSC), Geoff Outerbridge, at an adult sleep-away camp called Camp Good Life Project and we realized that we had a lot to talk about. He was developing an idea for a community Project for WSC that needed a teacher of yoga teachers with a strong anatomy and therapeutics background who happened to also have international volunteer experience (the flagship clinic is in Botswana, so being culturally aware and sensitive was very important). That is when I became the co-director/creator (along with my co-creator Barrie Risman and, since 2017, Jesal Parikh and Letizzia Wastavino) and particularly interested in Spine Care. However, the Yoga Project (YP) is not solely focused on Spine Care but also more generally on all musculoskeletal care, pain management, and active and preventative self-care.

PYI: Please tell us about the World Spine Care YOGA Project.

EM: I think the best way to start is with our mission and vision:

Mission

We are focused on building community capacity for low mobility populations by sharing the practices of Yoga as tools for management and prevention of musculoskeletal pain.

Vision

To globally inspire self-directed, self-led and self-sustaining communities, who experience low mobility, to use the practices of Yoga for active and preventative self-care and pain management.

We began in 2016 when Barrie Risman and I first rolled out the program in the flagship clinic in Shoshong (a village) and Mahalapye (a town) in Botswana. That first time, we worked with two different groups: one with higher mobility and one with lower mobility. We’ve since learned that the more mature group with lower mobility, who themselves benefited from the protocol, are the group that has kept the program going. They are also living in an area with a tighter community spirit. Because the Yoga Project is a community-oriented program, we learned, over time, how fundamental that tightly knit community is to the success of the program. They have taught us a lot and we have since gone back and offered level two of our protocol with more standing postures and breath and mindfulness.

Overall, this is how we function:

We work only with populations who have asked for a preventative/active self-care and pain management modal.

We work in our respective home countries and in global communities where World Spine Care has an existing presence with potential for expansion beyond WSC clinical modal into interested and supportive communities.

We train people who are interested in using the benefits of the Yoga Project protocol to contribute to their community and themselves.

We adapt to the individual needs of the communities we are working with; cultural norms and practices are incorporated into the program, i.e. dance, song, physical appropriateness of postures, posture names, etc.

We are a secular program, meaning that we are open to the beliefs of all the communities we serve and happily encourage worship where appropriate, but we do not come in with any religious overlay or agenda. We also teach that the history of the practice’s roots come from India and that there are many more practices, not included in the Yoga Project protocol, that can be explored individually.

We adapt the Yoga Project protocol as new information about mobility, physiology and psychology is made available to us through research.

We offer practices of mindfulness based upon research concerning mindfulness-based stress reduction and the 3000 years of Yogic practices for pain and stress management.

We offer practices of breath based upon vagal nerve research, etc., and the 3000 years of Yogic practices for pain and stress management.

We offer poses that explore stable, long-term, functional range of motion for lower mobility populations. We encourage adapting to offer low too no pain- movements to those experiencing pain.

We offer multiple levels of trainings as is appropriate for different levels of mobility and pain. Currently our offerings include: a level one training with a larger percentage of chair supported postures and a level two training with more standing postures and greater physical challenge.

We also offer our programs to MD, PT, OT and chiropractors as well as trained yoga instructors as continuing education to better serve their communities and patients.

We are an online resource for low mobility and pain populations world wide for at-home practice and capacity-building, using the practices of Mindfulness, Breath and Posture.

PYI: We understand that you train teachers in Botswana. Have the Botswana teachers found specific spinal needs in their communities?

EM: They themselves are dealing with a host of different spinal and musculoskeletal issues, pain and bio-psycho-social factors. We do not encourage or have time to specifically train our teachers to work with each different type of malady. Every issue they see and we have seen is multifactorial. The program is focused on keeping people mindfully active and offering stress management tools to help with pain management. Also, because we include such things as good biomechanics for getting in and out of a chair, seated posture work, etc., we are offering day-to-day applications of mindful movement. Basically, instead of working with individual conditions, we focus on mindfulness and svadyaya (self-reflection) as tools for choosing and working with movement that “feels good”.

Statistically, the most affected populations with chronic (long-lasting) pain due to musculoskeletal and specific spinal issues are women over 50 in developing nations, due to a host of reasons ranging from access to good health care options and self-care education to highly labor-oriented lifestyles (though that is never to say that someone who sits all day at work will suffer less pain). It is always a complicated mix of elements that includes: which musculoskeletal issues and pain issues arise as well as the bio-psycho-social factors in any given population, so I want to be careful about being too reductive.

That being said, here is a little bit from WSC website to help:

The Global Burden of Disease report was published in Lancet in December 2012 (Murray et al, Vos et al, 2012). In this report, the following information regarding spinal conditions was reported:

• Low back pain is the leading cause of disability.

• Neck pain is the fourth leading cause of disability.

• Low back pain and neck pain affect 1 billion people worldwide.

• Spinal pain contributes more to the global burden of disease (including death and disability) than: HIV, diabetes, malaria, stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, breast and lung cancer combined, traffic injuries, and lower respiratory infections.

PYI: In the recent past in America, yoga has been mostly available and marketed to a more privileged group of students. How do you suggest we work to diversify to provide yoga for all?

EM: Well, this really is the question! It certainly is on my mind all the time. I cannot propose to have the answer, though, because for me, I feel it is time to really listen, to ask questions and get curious, to listen again and then listen again and then to stand beside rather than in front of the voices that are rising in our community about intersectionality and inclusion. Perhaps through this process things will change: through good, true allyship.

The question I pose to any yoga business is this: what face, body, ability and/or sexual identity are you representing in your teaching staff and in your advertisements? How are you creating a sangha that feels safe and accessible to all the bodies you hope to serve in your community? Who is in your community? Have you asked what they want? If it is not a visible shift, I don’t think a shift can actually happen. If it is not a fundamental values shift, I don’t think a shift can happen.

PYI: Do you have any advice for therapeutic yoga teachers wishing to start their own not-for-profit initiative?

EM: Ask questions, listen and go slowly. Do not think you know what a community needs because something has served you or “the research says” or “the tradition says”. Listen to what people are actually asking for: what their bodies and hearts and minds are asking for. Be open to learning and adapting. Ask, observe, adapt and then ask again!

PYI: How can we donate to your initiative?

EM: On this page you can specifically donate to the Yoga Project. You can find us on Facebook and Instagram @worldspinecareyogaproject, where we offer pain management tools and active self care from our protocol.

If you are an MD, PT or YT and want to do a Work-A-Day for WSCYP on the 16th in honor or World Spine day, follow this link.

————————————

It was truly an honor to spend time with Erin and learn about her important and groundbreaking work incorporating yoga therapy into the work of the World Spine Care—the PYI community extends its thanks and appreciation to her and the healthcare professionals and dedicated communities with whom she works. We look forward to offering you more interviews and insight on the exciting work being done by our students and graduates in the coming months.

——————————————————————————————————-

Erin Moon, C-IAYT, is the lead teacher of Functional Anatomy 1 and a Mentor at PYI.

Molly Goforth is a yoga and meditation teacher and a student at Prema Yoga Institute. She specializes in accessibility and trauma-informed yoga teaching and practice.

Polyvagal Theory and Holistic Healthcare

Our nervous systems, unmediated, rule much of our life experience without conscious input from us. This can be good, but for many people it is not and we suffer emotionally, physically, mentally and in relationships. The Polyvagal Theory (PVT) provides a framework for understanding how our autonomic nervous system creates our experiences and suggests methods for mediating those processes. Because PVT is a theory about our autonomic nervous system, this research is impactful for yoga therapists, teachers and practitioners, because much of our access to our nervous systems is through our bodies. Yoga’s ability to intentionally influence our nervous systems is well documented.

PVT, introduced by Stephen Porges in 1994, is a new understanding of our autonomic nervous system that offers an explanatory model for a wide range of illnesses and conditions that we previously had little understanding of why they occur and therefore how to treat them. These include conditions as varied as depression, fibromyalgia, obesity, PTSD, asthma, anxiety, digestive issues, and back pain. PVT also offers vagal tone as a potential diagnostic tool for measuring health in specific contexts.

Our nervous systems, unmediated, rule much of our life experience without conscious input from us. This can be good, but for many people it is not and we suffer emotionally, physically, mentally and in relationships. The Polyvagal Theory (PVT) provides a framework for understanding how our autonomic nervous system creates our experiences and suggests methods for mediating those processes. Because PVT is a theory about our autonomic nervous system, this research is impactful for yoga therapists, teachers and practitioners, because much of our access to our nervous systems is through our bodies. Yoga’s ability to intentionally influence our nervous systems is well documented.

PVT, introduced by Stephen Porges in 1994, is a new understanding of our autonomic nervous system that offers an explanatory model for a wide range of illnesses and conditions that we previously had little understanding of why they occur and therefore how to treat them. These include conditions as varied as depression, fibromyalgia, obesity, PTSD, asthma, anxiety, digestive issues, and back pain. PVT also offers vagal tone as a potential diagnostic tool for measuring health in specific contexts.

You might be familiar with the old model for understanding our autonomic nervous system (ANS). It is binary: on or off, or rather either the sympathetic (fight-or-flight) part is engaged, or the parasympathetic (rest-and-digest) part is engaged. There is more nuance to this model, but essentially that is the view. What this view had no ability to explain were states like depression: clearly not an “active” state, like fight-or-flight, but also clearly not the happiness of rest-and-digest. Our ANS is never “offline,” so what state is it in when someone is depressed?

The Vagal Paradox

Back in 1992 Stephen Porges got a letter from a neonatologist in response to an article where Porges had written about “high cardiac vagal tone” as a measure of health. Vagal refers to the vagus nerve. The baby doctor noted to Porges that he had been taught that high vagal tone in infants indicated bradycardia (dramatic slowing of the heartbeat), a sign of distress that could quickly lead to death. This was the discovery of the Vagal Paradox: how on the one hand could high vagal tone indicate health and on the other be a sign of imminent death?

The vagus nerve was discovered and named by a Greek physician-philosopher-scientist, Galen, in the second century. What wasn’t discovered until the Vagal Paradox came to light, was that there is not one vagus nerve. There are two: the ventral vagus (VV) and the dorsal vagus (DV). The two nerves originate in the brainstem, but from different nuclei, and have different pathways in the body, and inervate different organs. According to Porges, “..the vagus nerve is not one nerve but a family of neural pathways” (Porges, p. 27)

The neonatologist was seeing high dorsal vagus (DV) tone that was mediating bradycardia and leading to the death of many babies. Porges was measuring respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA), which is the variation between each heartbeat, also called Heart Rate Variability (HRV), as a measure of health mediated by the ventral vagus (VV) nerve. This led Porges to inquire into our model of the autonomic nervous system and propose the Polyvagal Theory. He writes “[m]y motivation to solve the vagal paradox led to new conceptualizations of the autonomic nervous system and the formulation of the polyvagal theory.” (Porges, p. 6)

The PVT begins with the idea “that neurogenic bradycardia and RSA are mediated by separate branches of the vagus nerve.” (Porges, p.27). Many questions follow from this discovery. What else do these separate branches mediate? How are these branches related to the sympathetic (fight-or-flight) nervous system (SNS)? How do these three parts work together? Both ventral vagus and dorsal vagus are part of the parasympathetic nervous system. They do things other than stimulate action (the SNS does that). So, rather than two ANS states, Porges theorized that we (all mammals, actually) have three ANS states: Ventral Vagal (VV), Sympathetic (SNS), and Dorsal Vagal (DV).

The Polyvagal Theory

The understanding of what the SNS does didn’t change much from the old model. The first major difference is the nuanced understanding of the difference between VV and DV states. Porges introduced the term Social Engagement System to refer to when we feel safe and secure, we are open and happy and able to easily and productively engage with other people. This ability is mediated by the ventral vagal state. It is where we are alert and relaxed. This is where we want to be all of the time that we are not under a real threat.

To conceptualize the dorsal vagal state, remember the babies experiencing bradycardia, extreme slowing of the heart, their bodies were shutting down. Trauma researchers have described this state, often using the response of animals in the wild to paint the picture. Animals, when faced with mortal threat (the tiger is about to bite into the antelope) go limp, act dead, shutdown. This is not a conscious decision, but a nervous system response, the dorsal vagal response. This gave a new perspective to depression; perhaps depression is mediated by a dorsal vagal ANS response. Many illnesses and diseases, seen through the lens of PVT, seem quite different in terms of cause, and therefore treatment.

A few more pieces of the PVT are critical. The development of these parts of our ANS happened over time - evolutionary time. The dorsal vagal shutdown response is the oldest evolutionarily and sometimes described as reptilian. The SNS developed next and the ventral vagal was last and is exclusive to mammals. This hierarchy is not just in terms of history, but expresses itself in the current relationships between these parts of our ANS.

The Vagal Brake

The relationship between the parts of our ANS is most important in the concept of the vagal brake. The vagal brake refers to the action by the ventral vagus to slow down SNS or DV response and give the possibility of remaining in the VV state. Humans are best (happiest, healthiest, most productive) in the VV state and the body will seek to maintain VV state when possible (more on what it means to be in VV state below). However, life has challenges and obstacles which require the protective defenses mediated by the SNS and DV states. Sometimes we need to run to survive. Sometimes we need to greatly slow down our internal systems to focus energy on the minimum necessary for survival. However, once in the SNS state, it takes significant energy and time to regain VV state. It takes even more energy and time to recover from the DV state back to VV. Therefore, a healthy system tries to maintain VV state when possible and this is the role of the vagal brake.

I have read a lot of descriptions of our nervous system - from both the old and new models - that use analogies of survival in the wilderness to illustrate SNS fight-or-flight and DV shutdown. We don’t live like that anymore and I think those kind of analogies obscure modern day triggers and how we can get stuck in SNS or DV. Our beings are adaptive and we have these three to be able to adapt to our environments. We need all three and we need to be able to move between the states without getting stuck, with the possible exception of being “stuck” in ventral vagal. Our modern day triggers are increasingly created by ourselves and other people in social contexts: a friend glancing at their phone during lunch with you can trigger a slight dip towards SNS or DV; the ubiquitous pressure of cell phones present can keep us in SNS. Our nervous systems are constantly challenged to even know the VV state, as many people are chronically shifting just between SNS and DV, so much so that these states have become socially normalized.

The Sweet Spot: Ventral Vagal State

The ventral vagal state is when we are calm, our breathing is diaphragmatic, slow and steady. We are alert and happy. We are able to take in the faces and voices of other people. We are responsive in a socially engaging way. We are cooperative and collaborative. When we are like this, and the others around us are like this, we are happy, creative and productive.

Being around people in this state can put us in this state. This is called co-regulation and it starts with an infant’s relationship to its mother. Before words, there are faces and voices. When a baby cries, the baby is dysregulated - tired, hungry, wet, scared (missing mom). When the caregiver looks at, picks up, soothes by signing or talking, and addresses the baby’s physical needs, the baby becomes calm. The baby’s nervous system was regulated by the caregiver’s. This is the foundation of attachment theory. It is also something that happens between humans for their entire lives - one nervous system regulating another.

The ventral vagal state does not mean time when no problems arise. Problems and challenges continuously arise in life. In the ventral vagal state you will instinctually choose to meet those challenges with an open mind, awareness, collaboration, cooperation, calmness. If those strategies don’t work, that’s when the potential of shifting to SNS or DV occurs. Recovery from SNS or DV back to VV is critical. We are wired for it to happen naturally and with other people (co-regulation). For many people, this does not happen and they become stuck in SNS or DV, which, because their nervous system has made this choice, their perception and cognitive choices are limited, although they cannot perceive this. Their ANS is operating as if they are under threat and in danger, and that is the primary frame for every decision, thought, emotion and behavior.

Yoga is a remarkable practice for calming and regulating the nervous system. Although the ancient yogis did not have the terms that Porges has described in PVT, much of yoga can be viewed as seeking to regulate the nervous system and bring it into the ventral vagal state. Yoga is now described as integrative. It has always been, we just have these words for it now, and these words are important in bringing yoga therapy into service in broader healthcare contexts. Yoga treats the entire person and does not necessarily need to separate out, for example, obesity from depression, or acne from anger, or diarrhea from anxiety. It turns out, neither does the polyvagal theory. Dysfunction in the mind, body, and/or emotions, dysfunction in a human being can be seen through the PVT as dysregulation of the ANS. Shifting the frame of pathology opens the possibilities of new approaches to healing, even if some of those approaches are ancient.

Neuroception

Especially important for any kind of therapist is neuroception. Neuroception is a term coined by Porges in the development of PVT to name the process of the ANS scanning for safety and threat and then acting, by activating one of the three neural pathways, VV, SNS, or DV, as a response to the assessment of danger. “The autonomic nervous system is our personal surveillance system, always on guard, asking the question “Is this safe?” [It is] listening moment by moment to what is happening in and around our bodies and in the connections we have to others.” (Dana, p. 8) This is a kind of listening and responding and it happens below our conscious awareness. We have no control over it. Our ANS is in charge. “This is not the brain making cognitive choice. These are autonomic energies moving in patterns of protection. And with this new awareness, the door opens to compassion.” (Dana, p. 6)

Perception is managed through the senses and processed in the brain, cognitively, as in I see the red traffic light ahead of me, I perceive the light, its color and meaning to me as I drive toward it. Interoception is the sensing of one’s internal environment, as in when breathing diaphragmatically I sense my rib cage expanding and contracting with my breath. Proprioception is awareness of the position of the body, as in when I am swimming I am reaching my arm forward and then pulling it through the water underneath me. These three -- perception, interoception, and proprioception -- are cognitive. They involve sense organs for information, and that information is processed cognitively. This is not the case with neuroception, the “information processing” is done by the autonomic nervous system. “No matter how incongruous an action may look from the outside, from an autonomic perspective it is always an adaptive survival response. The autonomic nervous system doesn’t make a judgment about good and bad; it simply acts to manage risk and seek safety.” (Dana, p. 6)

The Autonomic Ladder as an Awareness Tool

Deb Dana, a clinical social worker, has created many tools based on her understanding of the PVT to help her clients understand their nervous system and heal. One of the most powerful of these tools she calls the Autonomic Ladder. It is an awareness tool. She teaches clients about each of the three ANS states: VV, SNS, and DV and then asks them to monitor where they are on the ladder throughout their day. Once clients have this in place she asks them to create two more tools: one that identifies triggers, for things that trigger one out of VV and into SNS or DV; “glimmers” - identification of things that one identifies with being in the VV state; and finally “resources,” where one lists internal and external resources available to move from SNS or DV back up the ladder to VV.

The ventral vagal state is the top of the ladder, it not only feels better to be in this state, but ventral vagal tone is highly correlated with overall health. How can you identify when you are in the VV state? You think about people important to you; you laugh and smile; you don’t feel rushed or pressured; you feel open to new ideas and creative; you are in nature; you are with people you care about or pets; you are listening to music; you feel relaxed yet aware. You are curious and have a sense of possibility and hopefulness. You feel grounded, in rhythm and connected. Dana notes that “[c]lients may be surprised by the unfamiliarity of this state.” (Dana, p. 27)

The middle rung on the ANS Ladder is SNS activation. Dana describes the SNS state as needing to do something NOW!, as feeling pressed for time, ignored, confused, or pushed to make a choice or take a side; as feeling responsible for too many people or things; as being around conflict. In SNS activation our negativity bias comes to the fore: neutral faces or situations seem dangerous to us in this state and we often misread social cues as negative. SNS brings strategies of confrontation or avoidance. SNS activation is “[n]ot limited to the act of physically engaging in violence, the fight response includes the full range of other behaviors aimed at changing things by force: verbal aggression in the form of sarcasm and abuse, passive aggression (opposing by not taking part), random aggression toward strangers, and wanton destruction of property. Similarly, flight is not only the act of running away -- it includes actively avoiding people, situations, or places. It can be simply withdrawing from social situations by watching television or taking part in other solitary activities, possibly driven by anxiety or panic attacks.” (Rosenberg, p. 51) “Some of the daily living problems can be anxiety, panic attacks, anger, inability to focus or follow through, and distress in relationships. Health consequences can include heart disease; high blood pressure; high cholesterol; sleep problems; weight gain; memory impairment; headache; chronic neck, shoulder, and back tension; stomach problems; and an increased vulnerability to illness.” (Dana, p. 11)

The bottom rung on the Autonomic Ladder is DV activation. Dana describes DV as believing you are without options, you feel trapped, unimportant, criticized, as if you don’t matter, as if you don’t belong. (Dana, p. 34) Dorsal vagal activation is about immobilization, not only physically, but emotionally, cognitively, energetically, digestively. Physically you may feel foggy, too tired to think or act, lost, empty. The world may feel empty. “Some of the daily living problems can be dissociation, problems with memory, depression, isolation, and no energy for the tasks of daily living. Health consequences of this state can include chronic fatigue, fibromyalgia, stomach problems, low blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, and weight gain.” (Dana, pp 11-12).

Discernment is critical to healing and health. Having an understanding of PVT and a tool like the Autonomic Ladder to use to figure out where you and your clients are in the moment is an important way to move from theory to practice. The fact that many of us are dysregulated a significant amount of the time is evidenced by the overwhelming disease and complaints related to stress and/or depressive behaviors, both in body and mind. Dana noted that many of her clients discover that they are unfamiliar with feelings of being in the ventral vagal state, which indicated that they spend very little time there indeed. With the speed and constancy of modern life with cell phones and digital screens almost everywhere it seems normal to have noise, pressure, and multiple things happening at the same moment. These can be cues for SNS activation for some, or overwhelm and DV activation for others -- and it has become normalized in Western society.

Western science and medicine has separated the mind from the body and although there is enormous evidence that one deeply affects the other, in practice, outside of integrative and complementary practices, we still have specialist for the mind and emotions and different specialists for the body. The PVT is another big piece of evidence in favor of integrative therapies. According to Rosenberg, “[i]n the conventional approach, however, doctors may be overlooking something.… The autonomic nervous system monitors and regulates the functioning of the visceral organs, and is a major contributing factor in determining our emotional state. However, doctors do not usually test its function” (Rosenberg, p.87).

Vagal Tone

Vagal tone can be measured by Heart Rate Variability (HRV) which is a measure of the difference from one beat to the next to the next (what is actually measured is called Respiratory Sinus Arrhythmia). If this sounds really small and difficult to conceptualize, it is. It is measured in milliseconds. You need a special monitor to detect and measure these subtle changes, although some body workers report being able to feel it when they take a client’s pulse. High vagal tone, which means there is a lot of difference between each beat, is correlated with multiple positive health measures. Rosenberg has come up with a simple test to see if the ventral vagus nerve is firing or not, at least pharyngeal branch function of the ventral vagus nerve, by checking if the arches next to the uvula and the uvula lift evenly (Rosenberg, p. 82-83). Since, we typically move in and out of the three states of the ANS throughout each day (and there are hybrid states, but that is beyond the scope of this article), a quick, easy to administer, low cost test for function is perhaps more useful than a precise but expensive measurement.

Yoga and Polyvagal Theory as Integrative Frameworks

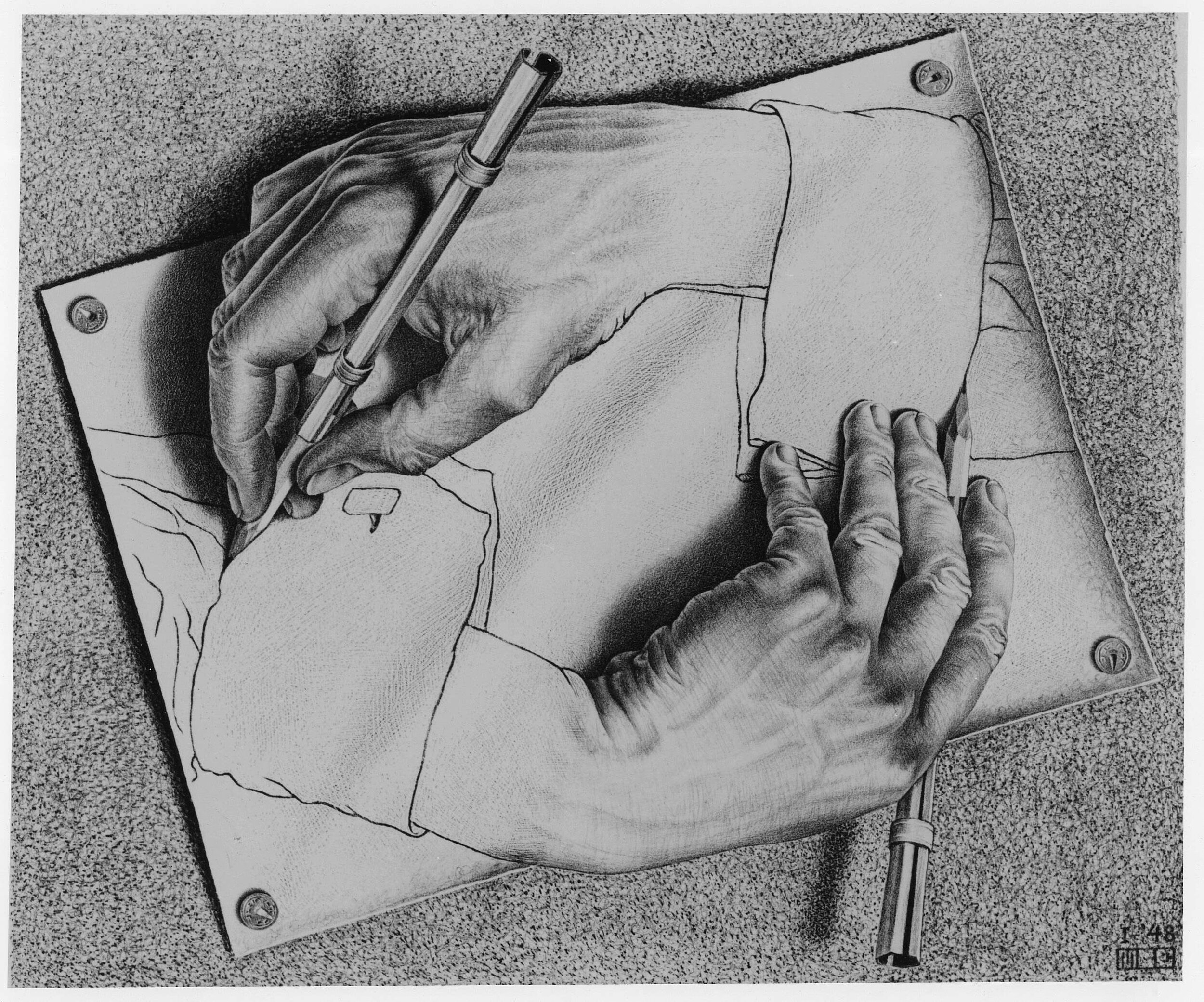

“The Polyvagal Theory also presents another dimension to our understanding of the autonomic nervous system. The autonomic nervous system not only regulates the function of our inner organs; these three circuits also relate to our emotional states, which in turn drive our behavior.” (Rosenberg, p. 30) With the PVT we have a lens that sees our body and our emotional states and our behaviors in the same view. We have an integrative framework. Yoga provides an integrative framework as well. The two, polyvagal theory and yoga, as frameworks for understanding human health, disease, and suffering have profound parallels.

Specifically, there is a correlation between the ANS states -- VV, SNS, and DV -- and what is known in yoga as the gunas. The gunas, there are three, are the qualities of material nature. Yoga holds that the cause of suffering (including, but not limited to what in Western medicine we call disease or illness, mental and physical) is our relationship, reaction to, and misidentification with material nature, which is comprised of the gunas. A classic formulation of this misidentification is the difference between “I am angry” vs. “I am experiencing anger” or “anger is arising in me.” At its most fundamental yoga is about learning to discern this difference in the many ways it shows up in life.

The gunas are sattva, rajas and tamas. Sattva is known as illuminating, calmness, ease, clarity. Rajas is the energy of activation, striving, change. Tamas is heavy, dull, not moving. Just these short descriptions beg comparison with ventral vagal, sympathetic, and dorsal vagal states. Indeed, Sullivan et. al. posit “PVT can be conceptualized as a neurophysiological counterpart to the yogic concept of the gunas.” (Sullivan et. al., p.1). The gunas are how material nature shows up: depression and ice cream are heavy, dull; anger and cayenne pepper are active, strident; meditation and apples are calm, illuminating.

Sullivan et. al. posit, “[b]oth PVT and the gunas provide a perspective to understand underlying foundations from which physical, psychological and behavioral attributes emerge. PVT provides insight into how underlying neural platforms are activated in response to perceived threat or safety … Yoga suggests that physical, psychological and behavioral attributes emerge from and are influenced by the underlying interplay of the gunas.” (Sullivan, et. al., p. 8). Not only is this interesting from a historical perspective (yoga is at least 2000 years old, and as mentioned above the polyvagal theory was introduced in 1994), but it suggests a way to translate the essential framework and methods of yoga into terms that are understood and accepted by Western medical and scientific practitioners.

Further, both systems -- PVT and the yoga gunas -- provide a holistic reframing of health and disease that is not reductive; specific and knowable physical, psychological and behavioral attributes can emerge from a neural state or through the predominance of a guna and can be influenced and changed by shifting either the neural state or the balance of gunas in predictable ways. Many yoga therapists and teachers have known through experience the value of the comprehensive methodology of yoga that spans its eight limbs for healing which is predicated on the deep integration, or indeed, oneness of our being as opposed to the reductionism that has defined Western medical practices. “PVT provides a neurophysiological explanation of the methods and techniques embedded in yoga.” (Sullivan, et. al., p. 11). It is not an overstatement to say that polyvagal theory is revolutionary in terms of our understanding of our autonomic nervous system. It holds many other, perhaps more radical, possibilities, not the least of which is the understanding and acceptance of holistic healthcare and yoga therapy in the West.

Image Credits:

● Vagus nerve CREDIT: https://www.thecut.com/2019/05/i-now-suspect-the-vagus-nerve-is-the-key-to-well-being.html

● Escher Hands - public domain

● Autonomic ladder from Dana, p. 57

● Gunas CREDIT: https://beyogi.com/the-guna-greatness/

Sources:

Dana, D. (2018). The Polyvagal Theory in Therapy: Engaging the Rhythm of Regulation. New York. W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Levine, P., Porges, S, and Phillips, M. (2015). Healing Trauma and Pain Through Polyvagal Science. E-book published on www. Maggiephillipsphd.com.

McCall, T. (2007). Yoga as Medicine: the yogic prescription for health and healing. New York. Bantam Dell.

Porges, S. (2011). The Polyvagal Theory: neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, self-regulation. New York. W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Rosenberg, S. (2017). Accessing the Healing Power of the Vagus Nerve: self-help exercises for anxiety, depression, trauma, and autism. Berkeley, California. North Atlantic Books.

Spindler, B. (2018). Yoga Therapy for Fear: Treating anxiety, depression and rage with the vagus nerve and other techniques. London, UK. Singing Dragon.

Stern, E. (2019). One Simple Thing: a new look at the science of yoga and how it can transform your life. New York. North Point Press.

Saraswati, S.S. (1976). Yoga Nidra. India. Yoga Publications Trust.

Sullivan, M.B., Erb, M., Schamlzl, L.,Moonaz, S., Taylor, J.N., and Porges, S. (2018). Yoga therapy and polyvagal theory: the convergence of traditional wisdom and contemporary neuroscience for self-regulation and resilience. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 12, article 67.

Sullivan, MB., Polyvagal Theory and the Gunas. Retrieved on 09.17.2019 from https://kripalu.org/resources/polyvagal-theory-and-gunas-qa-marlysa-sullivan

van der Kolk, B. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. New York. Penguin Books.

——————————————————————————————————-

Deb McDermott is a first-year student in Yoga Therapy at Prema Yoga Institute. She has been a Yoga teacher for 20 years and recently completed a 40-hour training on Trauma Center Trauma Sensitive Yoga (TCTSY) with David Emerson and Jenn Turner.